Thursday, May 29, 2008

Puerto Rican Obama Ad

Can any one interpret this for me? Three years of High School Spanish and all I know is soy and gasolino.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

The Problem With Talking to Iran

By AMIR TAHERI

May 28, 2008

In a report released this week, the International Atomic Energy Agency expressed "serious concern" that the Islamic Republic of Iran continues to conceal details of its nuclear weapons program, even as it defies U.N. demands to suspend its uranium enrichment program.

Meanwhile, presumptive Democratic presidential candidate Barack Obama – in lieu of a policy for dealing with the growing threat posed by the Islamic Republic – repeats what has become a familiar refrain within his party: Let's talk to Iran.

There is, of course, nothing wrong with wanting to talk to an adversary. But Mr. Obama and his supporters should not pretend this is "change" in any real sense. Every U.S. administration in the past 30 years, from Jimmy Carter's to George W. Bush's, has tried to engage in dialogue with Iran's leaders. They've all failed.

Just two years ago, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice proffered an invitation to the Islamic Republic for talks, backed by promises of what one of her advisers described as "juicy carrots" with not a shadow of a stick. At the time, I happened to be in Washington. Early one morning, one of Ms. Rice's assistants read the text of her statement (which was to be issued a few hours later) to me over the phone, asking my opinion. I said the move won't work, but insisted that the statement should mention U.S. concern for human- rights violations in Iran.

"We don't wish to set preconditions," was the answer. "We could raise all issues once they have agreed to talk." I suppose Ms. Rice is still waiting for Iran's mullahs to accept her invitation, even while Mr. Obama castigates her for not wanting to talk.

The Europeans invented the phrase "critical dialogue" to describe their approach to Iran. They negotiated with Tehran for more than two decades, achieving nothing.

The Arabs, especially Egypt and Saudi Arabia, have been negotiating with the mullahs for years – the Egyptians over restoring diplomatic ties cut off by Tehran, and the Saudis on measures to stop Shiite-Sunni killings in the Muslim world – with nothing to show for it. Since 1993, the Russians have tried to achieve agreement on the status of the Caspian Sea through talks with Tehran, again without results.

The reason is that Iran is gripped by a typical crisis of identity that afflicts most nations that pass through a revolutionary experience. The Islamic Republic does not know how to behave: as a nation-state, or as the embodiment of a revolution with universal messianic pretensions. Is it a country or a cause?

A nation-state wants concrete things such as demarcated borders, markets, access to natural resources, security, influence, and, of course, stability – all things that could be negotiated with other nation-states. A revolution, on the other hand, doesn't want anything in particular because it wants everything.

In 1802, when Bonaparte embarked on his campaign of world conquest, the threat did not come from France as a nation-state but from the French Revolution in its Napoleonic reincarnation. In 1933, it was Germany as a cause, the Nazi cause, that threatened the world. Under communism, the Soviet Union was a cause and thus a threat. Having ceased to be a cause and re-emerged a nation-state, Russia no longer poses an existential threat to others.

The problem that the world, including the U.S., has today is not with Iran as a nation-state but with the Islamic Republic as a revolutionary cause bent on world conquest under the guidance of the "Hidden Imam." The following statement by the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the "Supreme leader" of the Islamic Republic – who Mr. Obama admits has ultimate power in Iran -- exposes the futility of the very talks Mr. Obama proposes: "You have nothing to say to us. We object. We do not agree to a relationship with you! We are not prepared to establish relations with powerful world devourers like you! The Iranian nation has no need of the United States, nor is the Iranian nation afraid of the United States. We . . . do not accept your behavior, your oppression and intervention in various parts of the world."

So, how should one deal with a regime of this nature? The challenge for the U.S. and the world is finding a way to help Iran absorb its revolutionary experience, stop being a cause, and re-emerge as a nation-state.

Whenever Iran has appeared as a nation-state, others have been able to negotiate with it, occasionally with good results. In Iraq, for example, Iran has successfully negotiated a range of issues with both the Iraqi government and the U.S. Agreement has been reached on conditions under which millions of Iranians visit Iraq each year for pilgrimage. An accord has been worked out to dredge the Shatt al-Arab waterway of three decades of war debris, thus enabling both neighbors to reopen their biggest ports. Again acting as a nation-state, Iran has secured permission for its citizens to invest in Iraq.

When it comes to Iran behaving as the embodiment of a revolutionary cause, however, no agreement is possible. There will be no compromise on Iranian smuggling of weapons into Iraq. Nor will the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps agree to stop training Hezbollah-style terrorists in Shiite parts of Iraq. Iraq and its allies should not allow the mullahs of Tehran to export their sick ideology to the newly liberated country through violence and terror.

As a nation-state, Iran is not concerned with the Palestinian issue and has no reason to be Israel's enemy. As a revolutionary cause, however, Iran must pose as Israel's arch-foe to sell the Khomeinist regime's claim of leadership to the Arabs.

As a nation, Iranians are among the few in the world that still like the U.S. As a revolution, however, Iran is the principal bastion of anti-Americanism. Last month, Tehran hosted an international conference titled "A World Without America." Indeed, since the election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005, Iran has returned to a more acute state of revolutionary hysteria. Mr. Ahmadinejad seems to truly believe the "Hidden Imam" is coming to conquer the world for his brand of Islam. He does not appear to be interested in the kind of "carrots" that Secretary Rice was offering two years ago and Mr. Obama is hinting at today.

Mr. Ahmadinejad is talking about changing the destiny of mankind, while Mr. Obama and his foreign policy experts offer spare parts for Boeings or membership in the World Trade Organization. Perhaps Mr. Obama is unaware that one of Mr. Ahmadinejad's first acts was to freeze Tehran's efforts for securing WTO membership because he regards the outfit as "a nest of conspiracies by Zionists and Americans."

Mr. Obama wavers back and forth over whether he will talk directly to Mr. Ahmadinejad or some other representative of the Islamic Republic, including the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Moreover, he does not make it clear which of the two Irans – the nation-state or the revolutionary cause – he wishes to "engage." A misstep could legitimize the Khomeinist system and help it crush Iranians' hope of return as a nation-state.

The Islamic Republic might welcome unconditional talks, but only if the U.S. signals readiness for unconditional surrender. Talk about talking to Iran and engaging Mr. Ahmadinejad cannot hide the fact that, three decades after Khomeinist thugs raided the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, America does not understand what is really happening in Iran.

Mr. Taheri's new book, "The Persian Night: Iran From Khomeini to Ahmadinejad," will be published later this year by Encounter Books.

Monday, May 26, 2008

American Neighbor Convention Contest - SUBMIT NOW!

Students: If you have nothing better to do over the summer and would like to enter this contest I think there are many people in our community who would fit this description. This could be your You Tube trip! Let me know if you decide to do this. Peace.

Ellen Degeneres Vs. John McCain: Gay Marriage

Gay marriage legal in California and Massachusetts and John McCain dealing with the repercussions. How does John McCain do here? Do you support the legalization of gay marriage in your state?

Thursday, May 22, 2008

236.com: The Red Wings Guys

This is so funny! On a serious note, we did discuss in class the people directly behind the speaker and what if any message was being sent to viewers. So what is the message here? Go Wings!

Americans' Views on Abortion Remain Static

Okay, so you want to talk about abortion, well here is an iteresting poll on Americans views on abortion. Where are you on this poll? Legal always, under certain circumstances, never legal. Is this a big issue for you? Is it bigger than Iraq or the economy? Comments?

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

John McCain 2013

We talked about the spin off ads that may occur and low and behold guess what I found! I couldn't post the others for various reasons, but this one was post worthy.

Monday, May 19, 2008

What's Morally Acceptable in 2008?

Skeletor is at it again. I just found this interesting. How much will family values have an impact on this election? What are family values? Which candidate would have more support in the election if these were the only issues people voted on?

Family Footsteps

Interesting video by John McCain's daughter as she is vlogging with her dad on the campaign trail. Her you tube channel is mccainbloggette. She has a number of videos.

Barack Obama in Billings, MT

While we were in school on Monday, Barack Obama responded to McCain's video below with this speech. Nothing like a good old fashioned speech in the Israeli Knesset to get the foreign policy debate going between Obama and McCain.

John McCain Responds To Obama Saying Iran Is A

It is on! Hillary may not be out, but McCain and Obama are starting the general election campaign. More discussion about foreign policy along the same lines as below.

Sunday, May 18, 2008

McCain responds to Obama at NRA convention

Your comments about this topic. Who is better qualified to defend America? Again, I ask you, which candidates foreign policy do you most agree with?

Obama takes on McCain/Bush

Obviously this issues has drawn the interest of many of you, so here is Obama's response to the Bush Knesset speech. Watch this one first and then the McCain response to the Obama response. Post your continued comments on this topic.

Friday, May 16, 2008

Thursday, May 15, 2008

We Won! - Speech! Speech! Speech!

It is with great pleasure that I get to announce that the South Titan Government Blog has won the Blogger's Choice Award presented by the Ed in 08 campaign (see article). I have had some that have said this isn't really a blog in the purest sense, and I would agree, in that I am not personally reflecting on government or education. I would argue that this is the type of interaction, whether a blog or not, that students are asking for in the classroom of the 21st century.

The award for this blog really goes to the students, who have taken the time to post their thoughts and feelings on various topics throughout the year. I have seen incredible growth in the depth of their understanding and the quality of their comments on issues, politics and the world. These students are not only engaged politically, but they do so with an understanding that making flippant remarks will not suffice in a democracy. Substantiating their beliefs with evidence (or at least what they feel is evidence) has become more and more common. Gone are the days of criticizing grammar. All who enter the blog know they must proof or be called out. Therefore, I proceed onward with much fear and trembling (there is not a student alive who doesn't want to proclaim the errors of their teacher). Regardless, these students are some of the most amazing young people in America. Many volunteer in their community, hold a job, compete athletically and musically throughout the year. They are what is good about America. I feel humbled to have had the opportunity to work with them this year.

So where do we go from here? Great question. First it was the You Tube Debates, then Skypeing to Afghanistan, Israel and China and now the Blog of the Year! Feels like the only place to go is down.

So again I ask where do we go from here? I have never felt so motivated and excited to continue to find ways to become a better teacher in the 21st century.

Some of my goals for next year include:

1. Share Ideas - I want to share blogging, skypeing and other great ways to get students engaged with teachers. I mean this morning we spoke for free to an American student in China. Reading about China in a textbook is great, but talking live via video to someone living in China...That is where it is at!!! I think blogging would be an incredible addition to most if not all of our courses offered.

2. Incorporate Student Blogs - I want students to write their own submissions on the blog, not just comment. I think this can be easily done and will really get students discussing topics they find interesting.

3. Learn - Wikis, Live Streaming...I don't really know what is next? I know I want to try to find ways to connect students to experts from around the world via skype or whatever. Textbooks get outdated quickly. Having students discuss ideas and perspectives with experts, ambassadors, other students in real time is probably the next step. I am looking forward to learning.

Well before I sign off I just want to thank Mr. Josh Allen. Check out his blog on technology in the classroom it is called The Tech Fridge.

He is doing an amazing job helping teachers see potential for using technology to enhance the curriculum.

I also want to thank Mrs. Lisa Alfrey for sending me to my first NERDA conference. It helped me formulate some ideas, like blogging and skypeing.

Finally, I just want to thank the administration at our school, namely Dr. Enid Schonewise, for trusting me with trying so many new things in the classroom. I mean she let me use YOU Tube, Blogger and Skype all in one year! That is a risk that many principals, and dare I say even districts, are not willing to take.

So I accept this award on behalf of my students and colleagues at P.L. South High School in little ol' Papillion, Nebraska (pop. 17,703). If we can go global, so can you!

Drug Testing at Creighton Prep High School: Good Idea or Bad?

.gif)

BY DIRK CHATELAIN

WORLD-HERALD STAFF WRITER

Omaha Creighton Prep announced Tuesday that it will randomly test its athletes for performance-enhancing drugs, beginning this fall.

The all-boys school, which boasts a tradition of athletic prowess, will be the first in Nebraska to adopt a drug-testing policy of its kind.

Before participating in a sport, Prep students and their parents must sign a form consenting to year-round random testing. Students who don't consent won't be eligible. Students who fail a test must sit out one year.

Creighton Prep hopes the policy acts as a deterrent to steroid use and serves as a teaching tool about the dangers of performance-enhancing drugs, said Athletic Director Dan Schinzel.

"There are two reasons that schools hesitate to do this," Schinzel said. "No. 1, the cost, which we have found not to be an inhibiting factor. . . .

"The second reason is they think there's a cloud of suspicion that will come over their school. I don't think that's true at all. We don't think we have a problem. We're being proactive. We see this as an educational tool."

Other schools in Nebraska have tested athletes for illegal drugs, but Prep is the first to test for performance-enhancing drugs.

Administrators across the state applauded Prep's initiative but raised practical concerns about its execution.

Foremost may be this question: Who decides which kids are tested?

"You can't just pick them out for no good reason," said Steve Joekel, Millard West assistant principal for activities. "That's like throwing mud at the wall and hoping something sticks. It's only a good thing if you can apply it in a way that's equitable, practical and reliable."

Parents may approve of a policy in theory, said Alliance High School Assistant Principal Skip Olds, but opinions change when it affects their own kid.

"You better have your ducks in a row," Olds said. "They'll have a lawyer up there before you can blink an eye."

Participation in extracurricular activities isn't a right, Schinzel said, it's a privilege.

"From a legal standpoint," he said, "we don't have any concerns."

The testing process will work like this: Each calendar season, including the summer, the National Center for Drug Free Sport, which Prep has hired to administer the tests, will randomly select six to 10 athletes.

It sends the names to Schinzel. He contacts the athletes, informing them that they have 24 hours to visit a collection site and provide a urine sample.

The sample is sent to the testing organization, which analyzes it and contacts Schinzel with the results.

If an athlete fails the test or doesn't show up, he is ineligible to compete in any sport for one calendar year.

Creighton Prep will test 30 to 40 athletes per year. Each test will cost the school $100 to $150. Over the course of a year, Schinzel said, the bill would run $3,000 to $5,000.

"We don't see that being too great of a cost," he said.

New Jersey became the first state in 2006 to mandate random performance-enhancing drug testing in high school athletics. Florida, Texas and Illinois have followed. Schinzel expects Nebraska to adopt testing within the next decade.

"We wanted to get ahead of the curve," he said.

The issue of performance-enhancing drugs has been on schools' radar for a long time. But finding ways to conduct tests has proven touchy.

Joekel called it a "huge political hurdle to overcome," especially because of funding. Each dollar put into testing, Olds said, takes a dollar away from buying books.

Steroids have surfaced as a hot-button issue at every level of sport in the wake of major league baseball's doping scandal. Home run kings Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds and strikeout pitcher Roger Clemens, along with dozens of others, have been linked to steroids.

According to a University of Michigan report in 2006, 2.7 percent of high school seniors have used steroids at some point.

States that have adopted a drug-testing policy have found that it does deter kids from steroid use, but the problem wasn't as critical as some testing proponents suggested, said Jim Tenopir, executive director of the Nebraska School Activities Association. Tenopir spoke last month to a colleague in Texas, a state that began testing last year.

"To date," he said, "they've had one positive."

Last fall, Schinzel and Joe Ryberg, Creighton Prep dean of students, started working on a policy. They studied the random testing policies of the NCAA, which has been testing athletes since the 1980s. Their proposal won support of the Creighton Prep administration and a board of parents. Monday, the school sent letters explaining the policy to students' homes.

"We've had nothing but positive feedback," Schinzel said.

Schinzel said he hopes to negate potential conflicts by educating parents about testing procedures. Implementation is a tall task, though. Even the NCAA navigated a learning curve, Tenopir said.

Alliance's Olds doesn't think Creighton Prep's policy goes far enough.

In 1986, Olds designed a mandatory testing program not for steroids, but for marijuana, cocaine and other illegal drugs. It folded under pressure from the Nebraska Civil Liberties Union.

If he could, Olds said, he would still test his athletes for drugs, including performance-enhancing substances. But if you're going to take the time to employ a policy, test everyone, he said.

"Random is not the way to do it," Olds said. "If you're going to do one, do them all. Then you can look anybody in the eye and say, 'Our athletic department is clean.'

"With random testing, you can't say that. It's a Band-Aid."

Schinzel is confident that Creighton Prep's program will raise awareness. Prep won't test for illegal drugs — the school already has a testing policy in place for those — but it will detect the most common drugs on the NCAA's list of banned substances.

"All of us," Joekel said, "will be interested to see how it works."

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

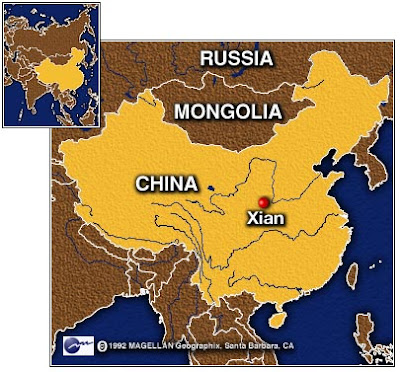

Live Skype Event to China

If you would like to attend a live Skype to Xian, China during 1st hour on Thursday, May 15th, you will need to get a pass from your 1st hour teacher signed. Once signed, head to room 2308 (Mr. Keller's room) for the event. We will be Skypeing with Ms. Rachel Perry, sister of Ms. Emily Perry, who has lived in Xian for the past 7 months. Come with questions about China's gov't, people, culture, climate, etc... I know you will enjoy the event. We will be, once again, using technology to reach across the world to understand our world better.

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Presidential IAT Test Results and Reflections

How did your test turn out? Which candidate did you most closely associate with? Do think this type of research can be a good indicator of people's true feelings on candidates? Was the test biased? What other factors do you feel could come into play with this test?

Click Here for Project Implicit

Monday, May 12, 2008

How Candidate Associations Affect Votes

Which of the associations listed has the most negative impact on the candidate for you personally and why?

Sunday, May 11, 2008

CNN - What If Barack Breaks Out?

Who will you support between Obama and McCain and why? Of course, Hillary may have something to say about this.

Saturday, May 10, 2008

Putin's Imperial Russia

Dmitry Medvedev may be the new president, but his predecessor is still the one with power.

By Garry Kasparov

May 10, 2008

MOSCOW --

Dmitry Medvedev was sworn in Wednesday as the president of Russia. Many reports have stated that this is his first elected office, an ignorant portrayal at best. The March 2 presidential election was widely recognized as a fraudulent charade. The presidency was assigned to Medvedev, in the same way he gained his previous titles -- as outgoing President Vladimir V. Putin's campaign manager, chief of staff and deputy prime minister. After the ceremony, Medvedev returned the favor and made Putin prime minister.

Putin has balked when asked if he would follow the tradition of government officials hanging the sitting president's portrait in their offices. But the joke going around is that he will indeed have one: a portrait of Medvedev in the president's office looking at a portrait of Putin.

According to the Russian Constitution, Medvedev is now in charge. But until there is evidence of his independence and authority, it is safe to assume that Medvedev still needs Putin's permission to use the Kremlin lavatory. The real "smooth transition of power" was moving Putin from the presidency to prime minister.

We can expect a few proclamations and perhaps even token policy changes. Unfortunately, the early signs show that Medvedev's statement about developing civil freedoms and ending "legal nihilism" were only a show for the West. Such displays are needed to offset elections with the results known in advance, lack of media freedom and businessgrowth that only benefits Kremlin loyalists. Otherwise, Putin's gang of oligarchs might lose easy access to billions in looted assets held in the West. So far, though, as Putin learned over the last eight years, there is no such danger. Russia pretends to be a democracy, and the United States and the European Union pretend to believe Russia is a democracy.

That morally repugnant pact is not working so well for those of us fighting for real democracy here. The day before Medvedev took power, several dozen people were arrested simply for being in the general area of a planned rally that had already been canceled. The police had promised that no one would be detained if the rally was called off; apparently they did not receive Medvedev's message about civil freedoms in time.

Oleg Kozlovsky, a member of the Other Russia opposition coalition leadership, was given 13 days in prison. Arrest reports for him came from two officers, each giving a different time and place of arrest. According to the judge, this curious fact "was not related to the case." A photojournalist working for the Russian paper Izvestia was sentenced to six days in prison for trying to do his job.

It is essential to resist the temptation to give this new/old Kremlin regime the benefit of the doubt. Let us not pretend Medvedev was truly elected or that we know anything about him. Far more is known about Barack Obama's former pastor. Medvedev is tainted from the start by his membership in Putin's dictatorial Kremlin regime. Action, not words, will establish whether he is his own man.

For that action to be meaningful, Medvedev must give immediate attention to these issues: He must free the long list of political prisoners who were jailed as Putin developed his dictatorship by KGB cronyism. Mikhail Khodorkovsky and other members of the Yukos Oil Co. management are the most prominent names, but there are also scientists convicted on spurious espionage charges and activists whose only crime was speaking out against the Kremlin. And the new president must act against the wave of hate crimes that have claimed 40 lives this year, mostly immigrants or nonwhite Russians. Homicidal neo-Nazi gangs roam the streets while pro-democracy marchers are locked up.

The basic human right of thinking and speaking one's mind has been drastically curtailed in Russia over the last eight years. The real test of Medvedev's presidency will be the way in which he deals with his most vocal critics. Other Russia is planning to hold a national assembly on May 17 in Moscow to facilitate dialogue on the most relevant problems and to determine a national agenda by bringing together representatives of diverse social forces, including those with opposite interests. We will also continue our street protests across Russia.

Will our activists still be harassed and detained for handing out pamphlets? Will our people still be followed by the security services? Will our peaceful actions again be violently dispersed by police? Will we again be denied access to legal counsel after being arrested? Will the courts continue to rubber-stamp our prosecutions? Until we have the answers to those questions, there is no reason to take Medvedev's word about anything.

Garry Kasparov, a former world chess champion, is a leader of the Other Russia coalition (theotherrussia.org).

Thursday, May 8, 2008

The Democratic Recession

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

Published: May 7, 2008

There are two important recessions going on in the world today. One has gotten enormous attention. It’s the economic recession in America. But it will eventually pass, and the world will not be much worse for the wear. The other has gotten no attention. It’s called “the democratic recession,” and if it isn’t reversed, it will change the world for a long time.

The term “democratic recession” was coined by Larry Diamond, a Stanford University political scientist, in his new book “The Spirit of Democracy.” And the numbers tell the story. At the end of last year, Freedom House, which tracks democratic trends and elections around the globe, noted that 2007 was by far the worst year for freedom in the world since the end of the cold war. Almost four times as many states — 38 — declined in their freedom scores as improved — 10.

What explains this? A big part of this reversal is being driven by the rise of petro-authoritarianism. I’ve long argued that the price of oil and the pace of freedom operate in an inverse correlation — which I call: “The First Law of Petro-Politics.” As the price of oil goes up, the pace of freedom goes down. As the price of oil goes down, the pace of freedom goes up.

“There are 23 countries in the world that derive at least 60 percent of their exports from oil and gas and not a single one is a real democracy,” explains Diamond. “Russia, Venezuela, Iran and Nigeria are the poster children” for this trend, where leaders grab the oil tap to ensconce themselves in power.

But while oil is critical in blunting the democratic wave, it is not the only factor. The decline of U.S. influence and moral authority has also taken a toll. The Bush democracy-building effort in Iraq has been so botched, both by us and Iraqis, that America’s ability and willingness to promote democracy elsewhere has been damaged. The torture scandals of Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo Bay also have not helped. “There has been an enormous squandering of American soft power, and hard power, in recent years,” said Diamond, who worked in Iraq as a democracy specialist.

The bad guys know it and are taking advantage. And one place you see that most is in Zimbabwe, where President Robert Mugabe has been trying to steal an election, after years of driving his country into a ditch. I would say there is no more disgusting leader in the world today than Mugabe. The only one who rivals him is his neighbor and chief enabler and protector, South Africa’s president, Thabo Mbeki.

Zimbabwe went to the polls on March 29, and the government released the results only last week. Mugabe apparently decided that he couldn’t claim victory, since there was too much evidence to the contrary. So his government said that the opposition leader, Morgan Tsvangirai, had won 47.9 percent of the vote and Mugabe 42.3 percent. But since no one got 50 percent of the vote, under Zimbabwe law, there must now be a runoff.

Tsvangirai and his Movement for Democratic Change claim to have won 50.3 percent of the vote and have to decide whether or not to take part in the runoff, which will be violent. Opposition figures have already been targeted by a state-led campaign of attacks and intimidation.

If South Africa’s Mbeki had withdrawn his economic and political support for Mugabe’s government, Mugabe would have had to have resigned a long time ago. But Mbeki feels no loyalty to suffering Zimbabweans. His only loyalty is to his fellow anti-colonial crony, Mugabe. What was that anti-colonial movement for? So an African leader could enslave his people instead of a European one?

What Mugabe has done to his country is one of the most grotesque acts of misgovernance ever. Inflation is so rampant that Zimbabweans have to carry their currency — if they have any —around in bags. Store shelves are bare; farming has virtually collapsed; crime by people just starving for food is rampant; and the electric grid can’t keep the lights on.

What can the U.S. do? In Zimbabwe, we need to work with decent African leaders like Zambia’s Levy Mwanawasa to bring pressure for a peaceful transition. And with our Western allies, we should threaten to take Mugabe’s clique to the International Criminal Court in The Hague — just as we did Serbia’s leaders — if they continue to subvert the election.

But we also need to do everything possible to develop alternatives to oil to weaken the petro-dictators. That’s another reason the John McCain-Hillary Clinton proposal to lift the federal gasoline tax for the summer — so Americans can drive more and keep the price of gasoline up — is not a harmless little giveaway. It’s not the end of civilization, either.

It’s just another little nail in the coffin of democracy around the world.

Wednesday, May 7, 2008

Who Will Tell the People?

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMAN

Published: May 4, 2008

Traveling the country these past five months while writing a book, I’ve had my own opportunity to take the pulse, far from the campaign crowds. My own totally unscientific polling has left me feeling that if there is one overwhelming hunger in our country today it’s this: People want to do nation-building. They really do. But they want to do nation-building in America.

They are not only tired of nation-building in Iraq and in Afghanistan, with so little to show for it. They sense something deeper — that we’re just not that strong anymore. We’re borrowing money to shore up our banks from city-states called Dubai and Singapore. Our generals regularly tell us that Iran is subverting our efforts in Iraq, but they do nothing about it because we have no leverage — as long as our forces are pinned down in Baghdad and our economy is pinned to Middle East oil.

Our president’s latest energy initiative was to go to Saudi Arabia and beg King Abdullah to give us a little relief on gasoline prices. I guess there was some justice in that. When you, the president, after 9/11, tell the country to go shopping instead of buckling down to break our addiction to oil, it ends with you, the president, shopping the world for discount gasoline.

We are not as powerful as we used to be because over the past three decades, the Asian values of our parents’ generation — work hard, study, save, invest, live within your means — have given way to subprime values: “You can have the American dream — a house — with no money down and no payments for two years.”

That’s why Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous defense of why he did not originally send more troops to Iraq is the mantra of our times: “You go to war with the army you have.” Hey, you march into the future with the country you have — not the one that you need, not the one you want, not the best you could have.

A few weeks ago, my wife and I flew from New York’s Kennedy Airport to Singapore. In J.F.K.’s waiting lounge we could barely find a place to sit. Eighteen hours later, we landed at Singapore’s ultramodern airport, with free Internet portals and children’s play zones throughout. We felt, as we have before, like we had just flown from the Flintstones to the Jetsons. If all Americans could compare Berlin’s luxurious central train station today with the grimy, decrepit Penn Station in New York City, they would swear we were the ones who lost World War II.

How could this be? We are a great power. How could we be borrowing money from Singapore? Maybe it’s because Singapore is investing billions of dollars, from its own savings, into infrastructure and scientific research to attract the world’s best talent — including Americans.

And us? Harvard’s president, Drew Faust, just told a Senate hearing that cutbacks in government research funds were resulting in “downsized labs, layoffs of post docs, slipping morale and more conservative science that shies away from the big research questions.” Today, she added, “China, India, Singapore ... have adopted biomedical research and the building of biotechnology clusters as national goals. Suddenly, those who train in America have significant options elsewhere.”

Much nonsense has been written about how Hillary Clinton is “toughening up” Barack Obama so he’ll be tough enough to withstand Republican attacks. Sorry, we don’t need a president who is tough enough to withstand the lies of his opponents. We need a president who is tough enough to tell the truth to the American people. Any one of the candidates can answer the Red Phone at 3 a.m. in the White House bedroom. I’m voting for the one who can talk straight to the American people on national TV — at 8 p.m. — from the White House East Room.

Who will tell the people? We are not who we think we are. We are living on borrowed time and borrowed dimes. We still have all the potential for greatness, but only if we get back to work on our country.

I don’t know if Barack Obama can lead that, but the notion that the idealism he has inspired in so many young people doesn’t matter is dead wrong. “Of course, hope alone is not enough,” says Tim Shriver, chairman of Special Olympics, “but it’s not trivial. It’s not trivial to inspire people to want to get up and do something with someone else.”

It is especially not trivial now, because millions of Americans are dying to be enlisted — enlisted to fix education, enlisted to research renewable energy, enlisted to repair our infrastructure, enlisted to help others. Look at the kids lining up to join Teach for America. They want our country to matter again. They want it to be about building wealth and dignity — big profits and big purposes. When we just do one, we are less than the sum of our parts. When we do both, said Shriver, “no one can touch us.”

Tuesday, May 6, 2008

China's Next-Generation Nationalists

By Joshua Kurlantzick

May 6, 2008

They're educated, richer and more aggressive toward the West.

As human rights protesters dogged the Beijing Olympics' torch relay around the world, as supporters of Tibet condemned the violent crackdown in Lhasa, and as Darfur activists demanded change in China's Sudan policy, Chinese young people worked themselves into a different form of righteous anger. In online forums and chat rooms, they blasted Beijing's leaders for not being tougher in Tibet. They agitated for boycotts against Western businesses based in nations that object to Beijing's policies, and they directed venomous fury against anyone critical of China.

The anger has even spread to American college campuses. In April, Chinese students at USC blasted a visiting Tibetan monk with angry questions about Tibet's alleged history of slavery and other controversial topics. When the monk tried to respond, the students chanted, "Stop lying! Stop lying!"

At the University of Washington, hundreds protested outside during a speech by the Dalai Lama, chanting, "Dalai, your smiles charm, your actions harm." When one Chinese student at Duke University tried to mediate between pro-China and pro-Tibet protesters, her photo, labeled "traitor," was posted on the Internet, and her contact information and her parents' address in China were listed for all to see.

The explosion of nationalist sentiment, especially among young people, might seem shocking, but it's been simmering for a long time. In fact, Beijing's leadership, for all its problems, may be less hard-line than China's youth, the country's future. If China ever were to become a truly free political system, it might actually become more, not less, aggressive.

China's youth nationalism tends to explode over sparks like the Tibet unrest. It burst into violent anti-American protests after NATO's accidental bombing of China's embassy in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, in 1999. (Most young Chinese I've met don't believe that the bombing was an accident.) Even after 9/11, a time when the governments of China and the United States were building a closer relationship, some young Chinese welcomed America's pain. "When the planes crashed into the World Trade Center, I really felt very delighted," one student told Chinese pollsters.

Youth nationalism exploded again into anti-Japan riots across China in 2005, after the release of Japanese textbooks deemed offensive in China for their apparent whitewashing of World War II atrocities. During the riots, I was working in Lanzhou, a gritty, medium-sized city in industrial central China. Day after day, young Chinese marched through Lanzhou and looked for shops selling Japanese goods to smash up -- though, of course, these stores were owned by local Chinese merchants.

Hardly uneducated know-nothings, young nationalists tend to be middle-class urbanites. Far more than rural Chinese, who remain mired in poverty, these urbanites have benefited enormously from the country's three decades of economic growth. They also have begun traveling and working abroad. They can see that Shanghai and Beijing are catching up to Western cities, that Chinese multinationals can compete with the West, and they've lost their awe of Western power.

Many middle-aged Chinese intellectuals are astounded by the differences between them and their younger peers. Academics I know, members of the Tiananmen generation, are shocked by some students' disdain for foreigners and, often, disinterest in liberal concepts such as democratization. University students now tend to prefer business-oriented majors to liberal arts-oriented subjects such as political science. The young Chinese interviewed for a story last fall in Time magazine on the country's "Me Generation" barely discussed democracy or political change in their daily lives.

Beijing has long encouraged nationalism. Over the last decade, the government has introduced new school textbooks that focus on past victimization of China by outside powers. The state media, such as the People's Daily, which hosts one of the most strongly nationalist Web forums, also highlight China's perceived mistreatment at the hands of the United States and other powers.

In recent years, too, the Communist Party has opened its membership and perks to young urbanites, cementing the belief that their interests lie with the regime, not with political change -- and that democracy might lead to unrest and instability. According to Minxin Pei of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, "The party showers the urban intelligentsia, professionals and private entrepreneurs with economic perks, professional honors and political access." In the 1980s, by contrast, these types of professionals and academics were at the forefront of Tiananmen protests.

The state media also increasingly highlight the problems of rural China -- China now has income inequality on par with many Latin American nations -- suggesting to urbanites the economic and political catastrophe that might befall them if these rural peasants swamped wealthy cities.

Now, though, according to Chinese officials, it appears that the Chinese government actually wants to tamp down nationalism. Some officials privately worry that nationalist protests, even ones targeting other countries, ultimately will transform into unrest against Beijing, like previous outbursts of patriotism in China before communist rule in 1949, which eventually turned into nationwide convulsions.

In 2005, Beijing initially fed the anti-Japan feelings with public statements. Then Beijing -- which depends on Tokyo as a crucial trading partner and source of aid -- tried to tamp down tensions by keeping much of the protest details out of the state media. Ultimately, though, Beijing had to roll out riot-control police in large cities. Similarly, after a 2001 collision between American and Chinese military planes that killed the Chinese pilot, Beijing struggled to keep street protests from erupting into riots.

In the long run, this explosive nationalism calls into question what kind of democracy China could be. Many Chinese academics, for example, believe that, at least in the early going, a freer China might become a more dangerous China. Able to truly express their opinions, young Chinese would be able to put intense pressure on a freer government to adopt a hard line against the West -- even, perhaps, to invade Taiwan. By contrast, the current Chinese regime has launched broad informal contacts with Taiwan's new rulers, including an April meeting between Chinese President Hu Jintao and incoming Taiwanese Vice President Vincent Siew -- contacts denounced by many bloggers. One day, Hu may find even he can't defend himself before a mob of angry Chinese students.

Joshua Kurlantzick is an adjunct fellow at the Pacific Council on International Policy and the author of "Charm Offensive: How China's Soft Power Is Transforming the World." He has reported on Asia for the last decade.

Sunday, May 4, 2008

Fairness, idealism and other atrocities

By P.J. O'Rourke

May 4, 2008

Well, here you are at your college graduation. And I know what you're thinking: "Gimme the sheepskin and get me outta here!" But not so fast. First you have to listen to a commencement speech.

Don't moan. I'm not going to "pass the wisdom of one generation down to the next." I'm a member of the 1960s generation. We didn't have any wisdom.

We were the moron generation. We were the generation that believed we could stop the Vietnam War by growing our hair long and dressing like circus clowns. We believed drugs would change everything -- which they did, for John Belushi. We believed in free love. Yes, the love was free, but we paid a high price for the sex.

My generation spoiled everything for you. It has always been the special prerogative of young people to look and act weird and shock grown-ups. But my generation exhausted the Earth's resources of the weird. Weird clothes -- we wore them. Weird beards -- we grew them. Weird words and phrases -- we said them. So, when it came your turn to be original and look and act weird, all you had left was to tattoo your faces and pierce your tongues. Ouch. That must have hurt. I apologize.

So now, it's my job to give you advice. But I'm thinking: You're finishing 16 years of education, and you've heard all the conventional good advice you can stand. So, let me offer some relief:

1. Go out and make a bunch of money!

Here we are living in the world's most prosperous country, surrounded by all the comforts, conveniences and security that money can provide. Yet no American political, intellectual or cultural leader ever says to young people, "Go out and make a bunch of money." Instead, they tell you that money can't buy happiness. Maybe, but money can rent it.

There's nothing the matter with honest moneymaking. Wealth is not a pizza, where if I have too many slices you have to eat the Domino's box. In a free society, with the rule of law and property rights, no one loses when someone else gets rich.

2. Don't be an idealist!

Don't chain yourself to a redwood tree. Instead, be a corporate lawyer and make $500,000 a year. No matter how much you cheat the IRS, you'll still end up paying $100,000 in property, sales and excise taxes. That's $100,000 to schools, sewers, roads, firefighters and police. You'll be doing good for society. Does chaining yourself to a redwood tree do society $100,000 worth of good?

Idealists are also bullies. The idealist says, "I care more about the redwood trees than you do. I care so much I can't eat. I can't sleep. It broke up my marriage. And because I care more than you do, I'm a better person. And because I'm the better person, I have the right to boss you around."

Get a pair of bolt cutters and liberate that tree.

Who does more for the redwoods and society anyway -- the guy chained to a tree or the guy who founds the "Green Travel Redwood Tree-Hug Tour Company" and makes a million by turning redwoods into a tourist destination, a valuable resource that people will pay just to go look at?

So make your contribution by getting rich. Don't be an idealist.

3. Get politically uninvolved!

All politics stink. Even democracy stinks. Imagine if our clothes were selected by the majority of shoppers, which would be teenage girls. I'd be standing here with my bellybutton exposed. Imagine deciding the dinner menu by family secret ballot. I've got three kids and three dogs in my family. We'd be eating Froot Loops and rotten meat.

But let me make a distinction between politics and politicians. Some people are under the misapprehension that all politicians stink. Impeach George W. Bush, and everything will be fine. Nab Ted Kennedy on a DUI, and the nation's problems will be solved.

But the problem isn't politicians -- it's politics. Politics won't allow for the truth. And we can't blame the politicians for that. Imagine what even a little truth would sound like on today's campaign trail:

"No, I can't fix public education. The problem isn't the teachers unions or a lack of funding for salaries, vouchers or more computer equipment The problem is your kids!"

4. Forget about fairness!

We all get confused about the contradictory messages that life and politics send.

Life sends the message, "I'd better not be poor. I'd better get rich. I'd better make more money than other people." Meanwhile, politics sends us the message, "Some people make more money than others. Some are rich while others are poor. We'd better close that 'income disparity gap.' It's not fair!"

Well, I am here to advocate for unfairness. I've got a 10-year-old at home. She's always saying, "That's not fair." When she says this, I say, "Honey, you're cute. That's not fair. Your family is pretty well off. That's not fair. You were born in America. That's not fair. Darling, you had better pray to God that things don't start getting fair for you." What we need is more income, even if it means a bigger income disparity gap.

5. Be a religious extremist!

So, avoid politics if you can. But if you absolutely cannot resist, read the Bible for political advice -- even if you're a Buddhist, atheist or whatever. Don't get me wrong, I am not one of those people who believes that God is involved in politics. On the contrary. Observe politics in this country. Observe politics around the world. Observe politics through history. Does it look like God's involved?

The Bible is very clear about one thing: Using politics to create fairness is a sin. Observe the Tenth Commandment. The first nine commandments concern theological principles and social law: Thou shalt not make graven images, steal, kill, et cetera. Fair enough. But then there's the tenth: "Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's house. Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife, nor his manservant, nor his maidservant, nor his ox, nor his ass, nor anything that is thy neighbor's."

Here are God's basic rules about how we should live, a brief list of sacred obligations and solemn moral precepts. And, right at the end of it we read, "Don't envy your buddy because he has an ox or a donkey." Why did that make the top 10? Why would God, with just 10 things to tell Moses, include jealousy about livestock?

Well, think about how important this commandment is to a community, to a nation, to a democracy. If you want a mule, if you want a pot roast, if you want a cleaning lady, don't whine about what the people across the street have. Get rich and get your own.

Now, one last thing:

6. Don't listen to your elders!

After all, if the old person standing up here actually knew anything worth telling, he'd be charging you for it.

P.J. O'Rourke, a correspondent for the Weekly Standard and the Atlantic, is the author, most recently, of "On The Wealth of Nations." A longer version of this article appears in Change magazine, which reports on trends and issues in higher education

The Rise of the Rest

Fareed Zakaria

NEWSWEEK

Updated: 2:24 PM ET May 3, 2008

It's true China is booming, Russia is growing more assertive, terrorism is a threat. But if America is losing the ability to dictate to this new world, it has not lost the ability to lead.

Americans are glum at the moment. No, I mean really glum. In April, a new poll revealed that 81 percent of the American people believe that the country is on the "wrong track." In the 25 years that pollsters have asked this question, last month's response was by far the most negative. Other polls, asking similar questions, found levels of gloom that were even more alarming, often at 30- and 40-year highs. There are reasons to be pessimistic—a financial panic and looming recession, a seemingly endless war in Iraq, and the ongoing threat of terrorism. But the facts on the ground—unemployment numbers, foreclosure rates, deaths from terror attacks—are simply not dire enough to explain the present atmosphere of malaise.

American anxiety springs from something much deeper, a sense that large and disruptive forces are coursing through the world. In almost every industry, in every aspect of life, it feels like the patterns of the past are being scrambled. "Whirl is king, having driven out Zeus," wrote Aristophanes 2,400 years ago. And—for the first time in living memory—the United States does not seem to be leading the charge. Americans see that a new world is coming into being, but fear it is one being shaped in distant lands and by foreign people.

Look around. The world's tallest building is in Taipei, and will soon be in Dubai. Its largest publicly traded company is in Beijing. Its biggest refinery is being constructed in India. Its largest passenger airplane is built in Europe. The largest investment fund on the planet is in Abu Dhabi; the biggest movie industry is Bollywood, not Hollywood. Once quintessentially American icons have been usurped by the natives. The largest Ferris wheel is in Singapore. The largest casino is in Macao, which overtook Las Vegas in gambling revenues last year. America no longer dominates even its favorite sport, shopping. The Mall of America in Minnesota once boasted that it was the largest shopping mall in the world. Today it wouldn't make the top ten. In the most recent rankings, only two of the world's ten richest people are American. These lists are arbitrary and a bit silly, but consider that only ten years ago, the United States would have serenely topped almost every one of these categories.

These factoids reflect a seismic shift in power and attitudes. It is one that I sense when I travel around the world. In America, we are still debating the nature and extent of anti-Americanism. One side says that the problem is real and worrying and that we must woo the world back. The other says this is the inevitable price of power and that many of these countries are envious—and vaguely French—so we can safely ignore their griping. But while we argue over why they hate us, "they" have moved on, and are now far more interested in other, more dynamic parts of the globe. The world has shifted from anti-Americanism to post-Americanism.

I. The End of Pax Americana

During the 1980s, when I would visit India—where I grew up—most Indians were fascinated by the United States. Their interest, I have to confess, was not in the important power players in Washington or the great intellectuals in Cambridge.

People would often ask me about … Donald Trump. He was the very symbol of the United States—brassy, rich, and modern. He symbolized the feeling that if you wanted to find the biggest and largest anything, you had to look to America. Today, outside of entertainment figures, there is no comparable interest in American personalities. If you wonder why, read India's newspapers or watch its television. There are dozens of Indian businessmen who are now wealthier than the Donald. Indians are obsessed by their own vulgar real estate billionaires. And that newfound interest in their own story is being replicated across much of the world.

How much? Well, consider this fact. In 2006 and 2007, 124 countries grew their economies at over 4 percent a year. That includes more than 30 countries in Africa. Over the last two decades, lands outside the industrialized West have been growing at rates that were once unthinkable. While there have been booms and busts, the overall trend has been unambiguously upward. Antoine van Agtmael, the fund manager who coined the term "emerging markets," has identified the 25 companies most likely to be the world's next great multinationals. His list includes four companies each from Brazil, Mexico, South Korea, and Taiwan; three from India, two from China, and one each from Argentina, Chile, Malaysia, and South Africa. This is something much broader than the much-ballyhooed rise of China or even Asia. It is the rise of the rest—the rest of the world.

We are living through the third great power shift in modern history. The first was the rise of the Western world, around the 15th century. It produced the world as we know it now—science and technology, commerce and capitalism, the industrial and agricultural revolutions. It also led to the prolonged political dominance of the nations of the Western world. The second shift, which took place in the closing years of the 19th century, was the rise of the United States. Once it industrialized, it soon became the most powerful nation in the world, stronger than any likely combination of other nations. For the last 20 years, America's superpower status in every realm has been largely unchallenged—something that's never happened before in history, at least since the Roman Empire dominated the known world 2,000 years ago. During this Pax Americana, the global economy has accelerated dramatically. And that expansion is the driver behind the third great power shift of the modern age—the rise of the rest.

At the military and political level, we still live in a unipolar world. But along every other dimension—industrial, financial, social, cultural—the distribution of power is shifting, moving away from American dominance. In terms of war and peace, economics and business, ideas and art, this will produce a landscape that is quite different from the one we have lived in until now—one defined and directed from many places and by many peoples.

The post-American world is naturally an unsettling prospect for Americans, but it should not be. This will not be a world defined by the decline of America but rather the rise of everyone else. It is the result of a series of positive trends that have been progressing over the last 20 years, trends that have created an international climate of unprecedented peace and prosperity.

I know. That's not the world that people perceive. We are told that we live in dark, dangerous times. Terrorism, rogue states, nuclear proliferation, financial panics, recession, outsourcing, and illegal immigrants all loom large in the national discourse. Al Qaeda, Iran, North Korea, China, Russia are all threats in some way or another. But just how violent is today's world, really?

A team of scholars at the University of Maryland has been tracking deaths caused by organized violence. Their data show that wars of all kinds have been declining since the mid-1980s and that we are now at the lowest levels of global violence since the 1950s. Deaths from terrorism are reported to have risen in recent years. But on closer examination, 80 percent of those casualties come from Afghanistan and Iraq, which are really war zones with ongoing insurgencies—and the overall numbers remain small. Looking at the evidence, Harvard's polymath professor Steven Pinker has ventured to speculate that we are probably living "in the most peaceful time of our species' existence."

Why does it not feel that way? Why do we think we live in scary times? Part of the problem is that as violence has been ebbing, information has been exploding. The last 20 years have produced an information revolution that brings us news and, most crucially, images from around the world all the time. The immediacy of the images and the intensity of the 24-hour news cycle combine to produce constant hype. Every weather disturbance is the "storm of the decade." Every bomb that explodes is BREAKING NEWS. Because the information revolution is so new, we—reporters, writers, readers, viewers—are all just now figuring out how to put everything in context.

We didn't watch daily footage of the two million people who died in Indochina in the 1970s, or the million who perished in the sands of the Iran-Iraq war ten years later. We saw little of the civil war in the Congo in the 1990s, where millions died. But today any bomb that goes off, any rocket that is fired, any death that results, is documented by someone, somewhere and ricochets instantly across the world. Add to this terrorist attacks, which are random and brutal. "That could have been me," you think. Actually, your chances of being killed in a terrorist attack are tiny—for an American, smaller than drowning in your bathtub. But it doesn't feel like that.

The threats we face are real. Islamic jihadists are a nasty bunch—they do want to attack civilians everywhere. But it is increasingly clear that militants and suicide bombers make up a tiny portion of the world's 1.3 billion Muslims. They can do real damage, especially if they get their hands on nuclear weapons. But the combined efforts of the world's governments have effectively put them on the run and continue to track them and their money. Jihad persists, but the jihadists have had to scatter, work in small local cells, and use simple and undetectable weapons. They have not been able to hit big, symbolic targets, especially ones involving Americans. So they blow up bombs in cafés, marketplaces, and subway stations. The problem is that in doing so, they kill locals and alienate ordinary Muslims. Look at the polls. Support for violence of any kind has dropped dramatically over the last five years in all Muslim countries.

Militant groups have reconstituted in certain areas where they exploit a particular local issue or have support from a local ethnic group or sect, most worryingly in Pakistan and Afghanistan where Islamic radicalism has become associated with Pashtun identity politics. But as a result, these groups are becoming more local and less global. Al Qaeda in Iraq, for example, has turned into a group that is more anti-Shiite than anti-American. The bottom line is this: since 9/11, Al Qaeda Central, the gang run by Osama bin Laden, has not been able to launch a single major terror attack in the West or any Arab country—its original targets. They used to do terrorism, now they make videotapes. Of course one day they will get lucky again, but that they have been stymied for almost seven years points out that in this battle between governments and terror groups, the former need not despair.

Some point to the dangers posed by countries like Iran. These rogue states present real problems, but look at them in context. The American economy is 68 times the size of Iran's. Its military budget is 110 times that of the mullahs. Were Iran to attain a nuclear capacity, it would complicate the geopolitics of the Middle East. But none of the problems we face compare with the dangers posed by a rising Germany in the first half of the 20th century or an expansionist Soviet Union in the second half. Those were great global powers bent on world domination. If this is 1938, as some neoconservatives tell us, then Iran is Romania, not Germany.

Others paint a dark picture of a world in which dictators are on the march. China and Russia and assorted other oil potentates are surging. We must draw the battle lines now, they warn, and engage in a great Manichean struggle that will define the next century. Some of John McCain's rhetoric has suggested that he adheres to this dire, dyspeptic view. But before we all sign on for a new Cold War, let's take a deep breath and gain some perspective. Today's rising great powers are relatively benign by historical measure. In the past, when countries grew rich they've wanted to become great military powers, overturn the existing order, and create their own empires or spheres of influence. But since the rise of Japan and Germany in the 1960s and 1970s, none have done this, choosing instead to get rich within the existing international order. China and India are clearly moving in this direction. Even Russia, the most aggressive and revanchist great power today, has done little that compares with past aggressors. The fact that for the first time in history, the United States can contest Russian influence in Ukraine—a country 4,800 miles away from Washington that Russia has dominated or ruled for 350 years—tells us something about the balance of power between the West and Russia.

Compare Russia and China with where they were 35 years ago. At the time both (particularly Russia) were great power threats, actively conspiring against the United States, arming guerrilla movement across the globe, funding insurgencies and civil wars, blocking every American plan in the United Nations. Now they are more integrated into the global economy and society than at any point in at least 100 years. They occupy an uncomfortable gray zone, neither friends nor foes, cooperating with the United States and the West on some issues, obstructing others. But how large is their potential for trouble? Russia's military spending is $35 billion, or 1/20th of the Pentagon's. China has about 20 nuclear missiles that can reach the United States. We have 830 missiles, most with multiple warheads, that can reach China. Who should be worried about whom? Other rising autocracies like Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states are close U.S. allies that shelter under America's military protection, buy its weapons, invest in its companies, and follow many of its diktats. With Iran's ambitions growing in the region, these countries are likely to become even closer allies, unless America gratuitously alienates them.

II. The Good News

In July 2006, I spoke with a senior member of the Israeli government, a few days after Israel's war with Hezbollah had ended. He was genuinely worried about his country's physical security. Hezbollah's rockets had reached farther into Israel than people had believed possible. The military response had clearly been ineffectual: Hezbollah launched as many rockets on the last day of the war as on the first. Then I asked him about the economy—the area in which he worked. His response was striking. "That's puzzled all of us," he said. "The stock market was higher on the last day of the war than on the first! The same with the shekel." The government was spooked, but the market wasn't.

Or consider the Iraq War, which has produced deep, lasting chaos and dysfunction in that country. Over two million refugees have crowded into neighboring lands. That would seem to be the kind of political crisis guaranteed to spill over. But as I've traveled in the Middle East over the last few years, I've been struck by how little Iraq's troubles have destabilized the region. Everywhere you go, people angrily denounce American foreign policy. But most Middle Eastern countries are booming. Iraq's neighbors—Turkey, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia—are enjoying unprecedented prosperity. The Gulf states are busy modernizing their economies and societies, asking the Louvre, New York University, and Cornell Medical School to set up remote branches in the desert. There's little evidence of chaos, instability, and rampant Islamic fundamentalism.

The underlying reality across the globe is of enormous vitality. For the first time ever, most countries around the world are practicing sensible economics. Consider inflation. Over the past 20 years hyperinflation, a problem that used to bedevil large swaths of the world from Turkey to Brazil to Indonesia, has largely vanished, tamed by successful fiscal and monetary policies. The results are clear and stunning. The share of people living on $1 a day has plummeted from 40 percent in 1981 to 18 percent in 2004 and is estimated to drop to 12 percent by 2015. Poverty is falling in countries that house 80 percent of the world's population. There remains real poverty in the world—most worryingly in 50 basket-case countries that contain 1 billion people—but the overall trend has never been more encouraging. The global economy has more than doubled in size over the last 15 years and is now approaching $54 trillion! Global trade has grown by 133 percent in the same period. The expansion of the global economic pie has been so large, with so many countries participating, that it has become the dominating force of the current era. Wars, terrorism, and civil strife cause disruptions temporarily but eventually they are overwhelmed by the waves of globalization. These circumstances may not last, but it is worth understanding what the world has looked like for the past few decades.

III. A New Nationalism

Of course, global growth is also responsible for some of the biggest problems in the world right now. It has produced tons of money—what businesspeople call liquidity—that moves around the world. The combination of low inflation and lots of cash has meant low interest rates, which in turn have made people act greedily and/or stupidly. So we have witnessed over the last two decades a series of bubbles—in East Asian countries, technology stocks, housing, subprime mortgages, and emerging market equities. Growth also explains one of the signature events of our times—soaring commodity prices. $100 oil is just the tip of the barrel. Almost all commodities are at 200-year highs. Food, only a few decades ago in danger of price collapse, is now in the midst of a scary rise. None of this is due to dramatic fall-offs in supply. It is demand, growing global demand, that is fueling these prices. The effect of more and more people eating, drinking, washing, driving, and consuming will have seismic effects on the global system. These may be high-quality problems, but they are deep problems nonetheless.

The most immediate effect of global growth is the appearance of new economic powerhouses on the scene. It is an accident of history that for the last several centuries, the richest countries in the world have all been very small in terms of population. Denmark has 5.5 million people, the Netherlands has 16.6 million. The United States is the biggest of the bunch and has dominated the advanced industrial world. But the real giants—China, India, Brazil—have been sleeping, unable or unwilling to join the world of functioning economies. Now they are on the move and naturally, given their size, they will have a large footprint on the map of the future. Even if people in these countries remain relatively poor, as nations their total wealth will be massive. Or to put it another way, any number, no matter how small, when multiplied by 2.5 billion becomes a very big number. (2.5 billion is the population of China plus India.)

The rise of China and India is really just the most obvious manifestation of a rising world. In dozens of big countries, one can see the same set of forces at work—a growing economy, a resurgent society, a vibrant culture, and a rising sense of national pride. That pride can morph into something uglier. For me, this was vividly illustrated a few years ago when I was chatting with a young Chinese executive in an Internet café in Shanghai. He wore Western clothes, spoke fluent English, and was immersed in global pop culture. He was a product of globalization and spoke its language of bridge building and cosmopolitan values. At least, he did so until we began talking about Taiwan, Japan, and even the United States. (We did not discuss Tibet, but I'm sure had we done so, I could have added it to this list.) His responses were filled with passion, bellicosity, and intolerance. I felt as if I were in Germany in 1910, speaking to a young German professional, who would have been equally modern and yet also a staunch nationalist.

As economic fortunes rise, so inevitably does nationalism. Imagine that your country has been poor and marginal for centuries. Finally, things turn around and it becomes a symbol of economic progress and success. You would be proud, and anxious that your people win recognition and respect throughout the world.

In many countries such nationalism arises from a pent-up frustration over having to accept an entirely Western, or American, narrative of world history—one in which they are miscast or remain bit players. Russians have long chafed over the manner in which Western countries remember World War II. The American narrative is one in which the United States and Britain heroically defeat the forces of fascism. The Normandy landings are the climactic highpoint of the war—the beginning of the end. The Russians point out, however, that in fact the entire Western front was a sideshow. Three quarters of all German forces were engaged on the Eastern front fighting Russian troops, and Germany suffered 70 percent of its casualties there. The Eastern front involved more land combat than all other theaters of World War II put together.

Such divergent national perspectives always existed. But today, thanks to the information revolution, they are amplified, echoed, and disseminated. Where once there were only the narratives laid out by The New York Times, Time, Newsweek, the BBC, and CNN, there are now dozens of indigenous networks and channels—from Al Jazeera to New Delhi's NDTV to Latin America's Telesur. The result is that the "rest" are now dissecting the assumptions and narratives of the West and providing alternative views. A young Chinese diplomat told me in 2006, "When you tell us that we support a dictatorship in Sudan to have access to its oil, what I want to say is, 'And how is that different from your support of a medieval monarchy in Saudi Arabia?' We see the hypocrisy, we just don't say anything—yet."

The fact that newly rising nations are more strongly asserting their ideas and interests is inevitable in a post-American world. This raises a conundrum—how to get a world of many actors to work together. The traditional mechanisms of international cooperation are fraying. The U.N. Security Council has as its permanent members the victors of a war that ended more than 60 years ago. The G8 does not include China, India or Brazil—the three fastest-growing large economies in the world—and yet claims to represent the movers and shakers of the world economy. By tradition, the IMF is always headed by a European and the World Bank by an American. This "tradition," like the segregated customs of an old country club, might be charming to an insider. But to the majority who live outside the West, it seems bigoted. Our challenge is this: Whether the problem is a trade dispute or a human rights tragedy like Darfur or climate change, the only solutions that will work are those involving many nations. But arriving at solutions when more countries and more non-governmental players are feeling empowered will be harder than ever.

IV. The Next American Century

Many look at the vitality of this emerging world and conclude that the United States has had its day. "Globalization is striking back," Gabor Steingart, an editor at Germany's leading news magazine, Der Spiegel, writes in a best-selling book. As others prosper, he argues, the United States has lost key industries, its people have stopped saving money, and its government has become increasingly indebted to Asian central banks. The current financial crisis has only given greater force to such fears.

But take a step back. Over the last 20 years, globalization has been gaining depth and breadth. America has benefited massively from these trends. It has enjoyed unusually robust growth, low unemployment and inflation, and received hundreds of billions of dollars in investment. These are not signs of economic collapse. Its companies have entered new countries and industries with great success, using global supply chains and technology to stay in the vanguard of efficiency. U.S. exports and manufacturing have actually held their ground and services have boomed.

The United States is currently ranked as the globe's most competitive economy by the World Economic Forum. It remains dominant in many industries of the future like nanotechnology, biotechnology, and dozens of smaller high-tech fields. Its universities are the finest in the world, making up 8 of the top ten and 37 of the top fifty, according to a prominent ranking produced by Shanghai Jiao Tong University. A few years ago the National Science Foundation put out a scary and much-discussed statistic. In 2004, the group said, 950,000 engineers graduated from China and India, while only 70,000 graduated from the United States. But those numbers are wildly off the mark. If you exclude the car mechanics and repairmen—who are all counted as engineers in Chinese and Indian statistics—the numbers look quite different. Per capita, it turns out, the United States trains more engineers than either of the Asian giants.

But America's hidden secret is that most of these engineers are immigrants. Foreign students and immigrants account for almost 50 percent of all science researchers in the country. In 2006 they received 40 percent of all PhDs. By 2010, 75 percent of all science PhDs in this country will be awarded to foreign students. When these graduates settle in the country, they create economic opportunity. Half of all Silicon Valley start-ups have one founder who is an immigrant or first generation American. The potential for a new burst of American productivity depends not on our education system or R&D spending, but on our immigration policies. If these people are allowed and encouraged to stay, then innovation will happen here. If they leave, they'll take it with them.

More broadly, this is America's great—and potentially insurmountable—strength. It remains the most open, flexible society in the world, able to absorb other people, cultures, ideas, goods, and services. The country thrives on the hunger and energy of poor immigrants. Faced with the new technologies of foreign companies, or growing markets overseas, it adapts and adjusts. When you compare this dynamism with the closed and hierarchical nations that were once superpowers, you sense that the United States is different and may not fall into the trap of becoming rich, and fat, and lazy.

American society can adapt to this new world. But can the American government? Washington has gotten used to a world in which all roads led to its doorstep. America has rarely had to worry about benchmarking to the rest of the world—it was always so far ahead. But the natives have gotten good at capitalism and the gap is narrowing. Look at the rise of London. It's now the world's leading financial center—less because of things that the United States did badly than those London did well, like improving regulation and becoming friendlier to foreign capital. Or take the U.S. health care system, which has become a huge liability for American companies. U.S. carmakers now employ more people in Ontario, Canada, than Michigan because in Canada their health care costs are lower. Twenty years ago, the United States had the lowest corporate taxes in the world. Today they are the second-highest. It's not that ours went up. Those of others went down.